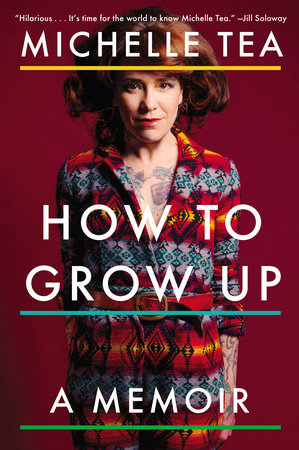

What does it mean to be a grown-up? I’m 32, and even though part of me still feels like a teenager, I’m slowly accepting the badge of “adult” and trying to wear it proudly. Whenever I feel like I don’t know how to be a grown-up—scared that it might mean trading in my sparkly nail polish, Baby-sitters Club obsession, and love of staying up all night writing—I look for guidance to the trailblazing feminist writers and artists that inspire me. Near the top of that list is Michelle Tea. Ever since I learned about Tea’s work in college, I’ve been drawn to her always-honest, often-hilarious, and usually heartbreaking memoirs, fiction and poetry that capture exactly what it’s like to be a working-class teen girl on acid in the suburbs, or a twenty-something queer punk navigating 90s San Francisco, infused with so much energy and intelligence and humor that it’s downright infectious to read. Michelle started the legendary all-women performance group Sister Spit in the 90s (and later the publishing imprint by the same name), built the SF-based literary organization/reading series RADAR Productions from the ground up, blogged about trying to get pregnant (and then about becoming a mother!) in her 40s, and founded a totally rad mothering magazine. She’s edited several fantastic anthologies, wrote a YA fantasy series, and so much more. Tea’s new memoir How to Grow Up details her beautifully unconventional path to where she is today—offering advice on jobs (“jobs are for quitting”), relationships, money (“I imagined the spirit of money as a tenderhearted fairy who longed to share herself with everyone”), battling addiction, and more. It may just be the guide to embracing a happy, healthy, uniquely awesome feminist adulthood that you, and I, need.

***

Marisa Crawford: Hi Michelle! I love your new book. I read it like the instruction manual that it is, getting super caught up in learning about your life and the lessons that came out of it for you, and eagerly applying those lessons to my own life—partly because I so admire you and the life that you’ve built for yourself, and partly because I’m definitely hungry for advice on how to live my not-so-traditional, feminist artist life in a world that doesn’t always welcome it. Did you or do you ever feel this desire for someone to tell you how to live your life? Is that at all part of why you decided to write a kind of growing-up manual for people like you? What made you want to write this memoir?

Michelle Tea: I ALWAYS want someone to tell me how to live my life! I’ve always taken the lead from my many fearless and hilarious friends whose lives have been perfectly unconventional. And I think I’ve gravitated to dates with “strong personalities” in the past because it can be such a relief to be around someone who seems to know what the next move is. Dating crazy people was helpful in that way too because a crazy person always has their next scheme up their sleeve, and it can be fun to go along on their ride for a minute. But eventually you have to figure out what your own deal is. I wrote the book at the suggestion of my agent, who seemed to think there was a story in how I got myself from Dirtbaggsville to the reasonable facsimile of an actual adult life I have now, and when I sat down to give it a whirl I was pleasantly surprised to find that there were some actual stories and lessons there.

MC: In your book, you say “If you grow up blue collar, you’re generally not expected to find a job that you love; love and job are two words that rarely show up in the same sentence. You endure your job.” Considering how you were raised to think about a job as something you merely “endure,” was it ever a struggle to get to a place of shamelessly valuing or prioritizing your artistic career? Did you ever feel pressure from your family or from the community where you were raised to stay on a more traditional, though maybe less enriching, career path?

MT: I think my blue collar background, and my family’s way of dealing with our economic situation, actually made it easier for me to embrace and value my writing. It wasn’t like I was opting out of some high-paying life by being a writer; I was always going to be broke, but this way I was broke but had something that brought meaning and joy into my life. Also, I was absolutely not pushed to go to college—in fact, I was lightly discouraged—so I never had student loan debt that forced me into a career I didn’t want in order to pay the bills. I like literally had no bills! When I needed a loan i could always find an excellent service but it really enabled me to focus all my time and energy and resources on writing and building literary community.

MC: You’ve done so many amazing things for the literary community, especially in San Francisco—starting Sister Spit, and RADAR, documenting SF’s 90s queer girl lit scene in various memoirs and anthologies, among other rad and important work. How has your relationship to your literary community changed over time?

MT: I’ve always felt that I’m part of many literary communities that sort of overlap sometimes. Because I started out at these mixed, often male-centric open mics I have community that began there, and then I have the more queer literary and feminist literary communities I helped to lasso together after. And the longer you do stuff the more people you meet and communities you get sort of welcomed into. Back when I was starting Sister Spit as a girls-only open mic I really felt that there needed to be literary space that was only for women, and I don’t doubt that those spaces are still useful, but over time I’ve become more and more interested in radical inclusion. Because I am queer, RADAR and Sister Spit is sort of defacto queer, and I like bringing all sorts of people into that space. I imagine it’s queer like a queer bar is queer—the space is queer, but all are welcome. I like curating straight and cis-gendered writers alongside queer writers. Let’s be real—often straight and cisgendered writers have an easier time building a career, and by curating queers who wind up being more underground alongside a straight person with a bigger career I hope that it opens up the queer writer to greater exposure and operates as a networking space for them. But really, I just get excited about writers and their writing no matter who they are, and it’s inspiring for me to curate them into events and expose the RADAR audience to them.

MC: How to Grow Up is your fifth memoir. How has your approach to writing a memoir evolved over time? What was it like to write this book for a more mainstream audience and publish it with a major press?

MT: Hmmmmmm. I guess what has changed is that after doing it for so long I really need to change it up somehow, in the stance or voice or perspective. Even though it was wicked scary to write for a more mainstream audience in How to Grow Up—I was terrified I sounded like a fucking cheezeball the whole time I was writing it (but I’m always afraid of something while I’m writing)—it was also great because I’d never written about my life in that particular way, looking back on it from the here and now, lessons learned and all that. I’ve always written from the totally other stance, dropping myself back into that time and place and ignoring anything I might have learned that might detract from the immediacy of the story. So it was cool to do something different. I’ve also never blatantly addressed the reader like I do in this book. I’ve done that in blogs, but not in a book, and that was different and fun. I have another “memoir” coming out in January, Black Wave, and in that I wrote in the third person about Michelle and fictionalized the shit out of it—like the world ends, and Michelle has an affair with Matt Dillon while living inside a used bookstore In Los Angeles during the end times. Gotta keep it fresh!

MC: Ummm, that sounds amazing. Do you consider writing about your own life a form of activism, and/or a feminist act?

MT: Hmmmmm, you know, I don’t. Someone at a recent RADAR—I think it was Faith Adiele, and I’m sorry if I’m mistaken—talked about activism as putting your body on the line, and I don’t put my body on the line with my writing. I’ve done activism, so I really can feel the difference between being out in the streets and exposing yourself to arrest and physical harm and possible humiliation, and being safely at home typing into my computer. I do think many forms of journalism can be activism, and I think the piece I wrote about Camp Trans and the gross “women-born-women” policy of the Michigan Women’s Music Festival, for The Believer, is as close to my writing being activist as possible. The stakes weren’t very high but I did go to Camp Trans and sneak inside the Festival with some other activists. I’d hoped the piece could be one more in a critical mass of writing and activism that helped to change cultural assumptions and bigotry against trans people. I do think that my writing is feminist, because I’m feminist! And hopefully that shows. But I don’t know if a woman writing about her own life is inherently feminist in 2015.

MC: You write in How to Grow Up about trying for a while to get pregnant, and now the book is out and you have a new baby! Does that feel amazing?

MT: It feels amazing and totally crazy—so much is happening all at once! But I feel like that’s how things happen for me so I’m totally not complaining, it’s amazing to have this fantastic BABY and it’s so fun to have a new book out and to get to do the fun part of being a writer— promoting it!

MC: Who are the bona fide grown-ups that you look up to?

MT: For sure my sister. She is the biggest grown-up in my life, and it’s funny because she’s my little sister but she just came out of the womb knowing so much more about the world than me. She was trying to explain to my mother how she could manage to buy a house when she was in like 6th grade. My wife, Dashiell, is super grown-up in ways that I am not at all, and it’s inspiring and informative to live with her. And really all my friends have managed to grow up in these weird, funny ways that illuminate possibilities. Watching them build their customized lives brick by brick is the greatest.

MC: Any friends in particular?

MT: Ali Liebegott, out in L.A. writing for the fantastic show Transparent. Beth Pickens, who has built her career around helping queer and marginalized artists get a piece of the pie. Tara Jepsen, who began skateboarding in her 30s. Beth Lisick, who has managed to keep writing and being a total weirdo as she’s raised her son.

MC: This was one of my favorite quotes from the book, about choosing to move into an apartment with younger roommates at 37 in part because of the tree in the yard:

Have you ever seen a persimmon tree? As all the other trees lose their leaves and begin their winter dying, the persimmon flares up brighter than any of them have ever been, bearing fruit, even. That was me. I wasn’t on the same timetable as the other trees in the garden, but I was alive, coming into a certain prime, even.

I love this so much. As a woman in particular, have you felt a lot of pressure to “act your age,” according to larger social norms? What’s your advice to other women who encounter those sentiments?

MT: I don’t know if I’ve received pressure to act my age—I think, because I spend my life within certain subcultures, not really in mainstream or normal spaces, that I’ve felt more pressure not to act my age, which made it harder, once I decided I wanted these sort of adult, normal, square things like security and serenity and stability, to even admit I wanted them, let alone to know how to even get them. But certainly my experience is not regular. We all know that women are pressured to fit into all sorts of cultural norms—their physical bodies get pressured, their interests, their sexualities, their lifestyles, for lack of a better word. But there are always women out there who are flamboyantly saying fuck you to all these things, and if you’re a person who is struggling under pressure to live in a way that is stressing you out, you can always access these people for inspiration.

Pingback: In the Media: 29th March 2015 | The Writes of Woman

Pingback: Women Working: 10 Poems for Labor Day - WEIRD SISTER

Pingback: On the Road: 20 Years of Sister Spit - WEIRD SISTER